Return to: The Weft

In 2001 and 2002, I interviewed family members about the Farm and its significance as a Puotinen home space. Looking back at the footage and listening to their responses, I’m struck by my oldest sister’s suggestion that the Farm is only temporarily yours.

Anne Puotinen

When I was interviewing her in 2002, this line stood out as a reminder that visiting the Farm, especially at the fourth of July, was the opportunity to participate in the (almost) one hundred year history of people who had experienced the Farm.

To be a part of the continuous chain of Puotinen family and friends that had built the farm buildings, worked the land, milked the cows, grown the potatoes, dug out the rocks in the fields, struggled to endure the harsh winters, picked apples off the trees, laughed in the kitchen, practiced cartwheels on the lawn, out-steamed each other in the sauna, sang and played the organ in the living room and celebrated family and the Amasa community.

Now, listening to her words in 2014, I understand them differently. The Farm is gone. It was sold in 2004. Her suggestion that the Farm is only temporarily yours was a warning that its presence in our lives is fragile and fleeting. It won’t be there forever. And, it wasn’t. Only two years after that interview, our parents had to sell it.

Of course, even without the Farm, the Puotinen history still exists. But, without the physical space to return to every year, we don’t celebrate that history. We don’t collectively retell the stories of life on the Farm. That continuous chain, if not broken, has weakened after losing the link between the Puotinen family and the farm house and 80 acres of land. I find myself struggling to figure out how to repair it.

What happens to that chain of people now that the Farm is gone? Is it broken?

Maybe one way to start the repairing process is to provide space for acknowledging and mourning the loss of that physical link between the Farm land and the Puotinen family.

In this Weft, I’m giving an account of losing the Farm. This account focuses less on the tragedy of the loss and more on its inevitability as I trace how Puotinen family members have negotiated their tenuous relationship to the Farm in five parts: 1. not my time…yet; 2. preserve, let rot, remove; 3. anticipating loss; 4. difficult decisions and 5. on not forgetting.

Restart Story

not my time…yet

Anne Puotinen

During the second round of interviews with family members in 2002, I posed the following questions: “How do you fit into the Farm and its history? What has it given to you? What have you given to it?”

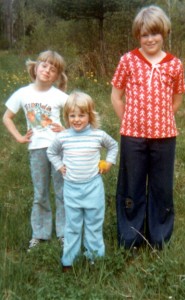

Both Judy and Anne suggested that their contributions were tied to a future when it was their turn to take responsibility and make their mark. Until that time, they needed to respect the visions of past generations and wait for when the property was theirs.

Judy Puotinen

According to Judy, waiting could be difficult. She recalls visiting the Farm for years, from the early 1960s until Grandpa Kully died in 1992, and not being allowed to explore any of the rooms or buildings. (For more on this story, watch this clip.) And the waiting could take a long time. Decades. At one point in her interview, Judy describes Grandma Ines’s experiences of living on the Farm while Kully’s parents were still alive:

Judy Puotinen

But even though waiting was hard, it felt important and necessary. It offered the promise of making a meaningful contribution to the Puotinen family and of honoring the labor of past generations.

Timeline detailing the waiting process for 2nd, 3rd and 4th generation Puotinens.

And it was exciting too. Not yet taking responsibility for the Farm was a chance to imagine new possibilities for it, to dream up, sometimes impossible or impractical, visions for its future.

What do you do when the Farm is gone before your time?

When the Farm was sold in 2004, the waiting was over, but so was the chance to take responsibility for it. And so was the future that we expected we’d have there.

an unimaginable future

Being at the Farm always inspired third and fourth generation Puotinen family members to dream about its future, to imagine new methods for building on or transforming important Puotinen family values. Was it the beautiful landscapes of the front and back 40 acres? The (almost excessive) quiet and solitude that being on a backroad in a remote area of the upper peninsula of Michigan created? The entrepreneurial spirits of Elias and Kaleva that permeated the farmhouse and its buildings? The sense of obligation to community that was present in so many of the stories about Elias, Kully and Ines that were told and retold each time we visited?

If you had 80 acres in the UP, what would you do with it?

When I interviewed family members about the Farm’s future in 2001 and 2002, they had many visions: A boys’ ranch. An artist’s retreat. A workspace for weaving. A gathering place for friends and family.

Watching these interviews again, over ten years later, I feel the force of our loss. We imagined the Farm would be the place where we could always go to “strengthen the family bond” and “work on our spirits,” individually and collectively. And, in the early 2000s, that’s what we did there. We met at the Farm and reconnected, eating wonderful meals, discussing great books and playing epic games of volleyball and whiffleball. We took peaceful hikes through the front and back 40 fields and celebrated “Fourt” July in Amasa. And, our kids played together. Since the loss of the Farm, we’ve had increasingly fewer opportunities to connect.

In my vision for the Farm’s future, the past was important. More so than any specific plan for what to do with the Farm, I wanted to make sure that I would never forget the place or the people. I wanted to honor the traditions and keep the spirit of the Puotinens alive to pass onto future generations. Is this possible without the physical space of the Farm? I hope so.

My vision for the Farm’s future was broad and a bit unclear. Maybe that’s because the Farm always seemed to transcend time. It didn’t really have a future or a past; it just was…the Farm. My best friend Jenny described the Farm as “the place where time stood still.” I liked that description. Having never lived in the same place for more then five years, I needed the sense of timelessness, of continuity that the Farm provided. It was my home and the place where I went to reaffirm my Sara-ness. (For more on the importance of the farm for my sense of Sara-self, see the story, “The Mirror.” )

Of course, the idea that the Farm was “the place where time stood still,” was an illusion; the Farm didn’t stand still. It was in a slow (and sometimes not so slow) state of decay.

Decaying buildings and landscapes could be found throughout the 80 acres.

And the Puotinens who were responsible for it, needed to make critical decisions about how to maintain the land and the buildings. They needed to decide what to preserve, what to let rot and what to remove.

Restart Story

preserve, let rot, remove

Art Puotinen

The Farm was a lot of work, especially for those who were responsible for it. Art grew up doing that work. After he left the Farm and went off to college, whenever he came back to visit, Kully would ask him to help out with various projects around the Farm. Art would grudgingly agree:

Art Puotinen

Judy Puotinen

When he and Judy inherited the property in 1992, they did even more work, making critical decisions about what to keep, what to repair and what to trash.

What do you preserve? Let rot? Remove?

How do we make these choices? When is it important to hold onto things (memories, buildings, artifacts)? And when is it necessary to let them go? What do we want to remember (preserve) about the Puotinen heritage and family history? What can or should we forget (let rot/remove)? Judy recalls confronting these questions starting in 1992:

Judy Puotinen

Until I interviewed my family members in 2001 and 2002, I didn’t think much about all that my parents had to do to maintain or improve the Farm. The difficult choices that they had to make about how to best honor the spirit of the Farm. The endless work they had to do to ensure that they could pass the Farm on to me, my sisters and our families. To me, the Farm was where I went to retreat and relax. But to my parents, especially my Dad, the Farm was a space filled with never-ending projects.

Art Puotinen

While the 3rd generation did most of the work, the 4th generation helped out too:

During the process of watching through the interviews and shaping the stories into two digital videos in 2001-2002, I encountered a reoccurring theme from my parents: The Farm was a treasure and a burden. It was a treasure for our family, a place to connect with each other and remember our history. But, it was also a burden—a money and an energy drain.

Back then in 2001, I saw this theme as good for my video stories; it was an opportunity to highlight one tension experienced at the Farm between celebrating the joyful spirit of the place and enduring its difficult demands. I didn’t seem to realize (or did I?) that my parent’s troubled understanding of the Farm hinted at the unsustainability of keeping the property, that their comments about the Farm as a treasure and a burden were anticipating the loss of the Farm just three years later.

Restart Story

anticipating loss

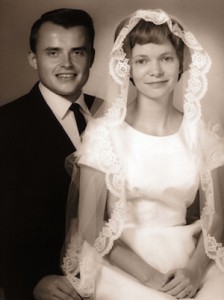

I was inspired by my graduate work on identity, home and storytelling, to conduct the video interviews up at the Farm in 2001 and 2002. I enlisted my husband Scott Anderson to help; he shot approximately 20 hours of footage of the Farm, its buildings and the surrounding 80 acres of land.

Out of that footage, Scott and I created two short documentaries about the Farm and its importance as a home space for the Puotinen family. The first one was dedicated to the Farm. The second one to my favorite storyteller, my mom.

In 2004, my parents sold the Farm. In 2005, my mom was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. She died in 2009.

After the Farm was sold and my mom died, I was very reluctant to create any more digital stories. I wondered: Was I inspired to create these stories only because I was unwittingly anticipating the loss of my mom and the Farm? What might happen to the subject of my next story?

Although my first reactions to the news that my parents had to sell the Farm were shock and sadness, I fairly quickly resigned myself to the loss. Maybe that resignation was because, deep down, I already understood the inevitability of the Farm being sold. I had been anticipating it for years. Unconsciously my interest in documenting the Farm must have come, at least partially, from that deeper awareness that one day it would be gone and I would need to gather up and preserve images, stories, and footage so that it would never be forgotten.

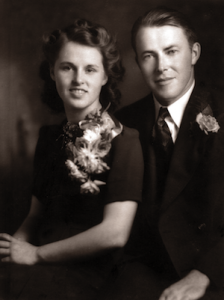

Many Puotinens that came before me felt the urge to store up memories in anticipation of losing the Farm, like my great-grandma Johanna. In their stories about the Farm, both of my parents recounted Johanna’s efforts to remember the front 40 wood line over the winter:

JOHANNA and the WOOD LINE

Art’s version: A sad remembrance had to do with walking in the field with my grandmoher Johanna. When I was a little guy she took me out there and as we were walking she began to make a shuddering sound. When I returned to the farmhouse with her and my mother, I said to my mother privately, “what was that strange sound grandmother was making?” And my mother said, “Well, she knows winter is coming and she hopes she survives another winter here on the farm.

Judy’s version: She would go out in the fall before the snow flew and stand and look at the wood line and make this clucking noise. And Ines said when she was a young bride it scared her to death. What was this women doing? So finally after she got more comfortable she asked her and Johanna said, “Well, I’m getting old now and I’m wondering if this the last winter I will ever spend so I’m taking in this wood line, how it looks so I can remember it all winter.

how do you tell your stories?

I remember that wood line and many other landscapes around the property. Thankfully, because of the video footage Scott and I captured, I won’t ever completely forget them:

Landscapes.

What was it about these farm landscapes that gave me comfort in times of uncertainty or grief?

Like Johanna, and my mom, I often gazed across the fields at the trees that outlined the woods of the back 40. While my gaze wasn’t always prompted by grief or the anticipation of loss, in key moments, like when I was recovering from a miscarriage or saying goodbye to the Farm for the final time, I sought out a vision of that wood line to give me strength and comfort:

Video footage of the front 40 with a focus on my favorite tree. I liked how it was taller than the others; it disrupted the tree line.

sara’s stories

story one. In the spring of 2002, I thought I had miscarried and needed to take the train to the doctor’s office. I remember sitting on the train, closing my eyes and visualizing the Farm and the front 40 wood line. That image of the wood line helped to calm me as I traveled towards the news that I was no longer pregnant.

story two. In September of 2004, I looked at the wood line just minutes before I left the Farm forever. Standing on my favorite rock, the big one by the grain shed that was almost completely buried in the ground, I tried to take in the view, knowing I’d never experience it the same way again.

Why did my parents decide to sell the Farm when it meant so much to the family? That decision was not a simple or a single one. And it really wasn’t one that was entirely under their control. As I look back at the chain of events and decisions made by Puotinen family members over the years, I’ve come to see the inevitability of the Farm being sold.

Restart Story

difficult decisions

In addition to making critical choices about how to deal with an aging farm property, second and third generation Puotinens struggled with other difficult decisions over whether or not to stay on the property, who would take responsibility for it when older generations could no longer do so and how to make it financially viable in the midst of numerous economic hardships.

To Stay or Leave?

Art Puotinen

When confronted with the decision of whether or not to leave the Farm, my Grandpa Kully chose to stay. Out of 12 siblings, he was the only one who wanted or was willing to. Born on the property in 1912, he lived almost his entire life there. It wasn’t until Grandma Ines died in 1990 that he left. In contrast, my Dad was encouraged, especially by his mom Ines, to leave the Farm. He went off to college in Rock Island, Illinois in 1959 and then only came back for brief visits until he and Judy moved back there for the fall and winter of 2002.

Art Puotinen

Who takes responsibility?

the decision

[From Ines Puotinen’s memoir.] In 1943 Grandpa and Grandma celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary. We had a celebration at the church and a very nice program. Emil was living in Astoria at the time and he came home for the occasion. Enroute home his suitcase was lost and so he had only the clothes he had on, so he did not have a suit to wear. Kully had a gray suit and he got busy and adjusted for Emil to wear and Emil like it so well he bought it later from Kully. Emil was the announcer at the program and it all went real well. There were a lot of people from many areas. Many pictures were taken and at the time Kully would develop pictures. In fact, when Art was little and we had this lovely dog, Lassie, Kully took many pictures which he developed.

Most of the family were home for the 50th anniversary and they felt that was a good time to discuss family affairs. A concern for most was that Grandma and Grandpa were getting along in years and what would become of the home and who would take care of them. No one else was interested in farming and so it was decided that Kully and I would remain on the Farm and that grandma and grandpa would have a home here for as long as they lived. There was a mortgage on the Farm that Eino had taken over and we were to finish paying the mortgage.

Most of the family were home for the 50th anniversary and they felt that was a good time to discuss family affairs. A concern for most was that Grandma and Grandpa were getting along in years and what would become of the home and who would take care of them. No one else was interested in farming and so it was decided that Kully and I would remain on the Farm and that grandma and grandpa would have a home here for as long as they lived. There was a mortgage on the Farm that Eino had taken over and we were to finish paying the mortgage.

Grandma and Grandpa went to sleep early. After several hours of talk and drinking numerous cups of coffee, the rest of us went up to sleep. Ellen, Art, and I slept in one room. Ellen and I couldn’t fall asleep because of heartburn after drinking all that coffee so we came downstairs to mix some bicarbonate of soda to drink for relief. When we came down Eino was roaming around and so Ellen said that we might as well fix him some, too, but when we brought it to him, he said that was not the problem. He couldn’t sleep because he was supposed to sleep with Emil and Emil was snoring so loud that Eino couldn’t sleep.

This excerpt from Ines’s memoir makes me curious. Nestled in between humorous stories about Emil—first he loses his suitcase, then he’s snoring so loudly that Eino can’t sleep—is a brief, matter-of-fact sentence about how it was decided that Ines and Kully would take over the Farm and take care of Elias and Johanna. Was this conversation difficult? Contentious? Did Kully and Ines struggle with their decision to become responsible for the property and for taking care of ailing parents? Were any of the other siblings upset about leaving and therefore losing the Farm?

Throughout her memoir, my grandmother rarely provides details about difficult events. This story about the decision is no different. Yet, her mention of drinking lots of coffee and not being able to sleep after the family meeting suggests that the decision to accept responsibility for the Farm was a hard one to make.

I can only imagine that it was. When it came time for Mom and Dad to decide what to do with the Farm, we (Mom and Dad, Anne and Yaz, Marji and Glenn, Sara and Scott) didn’t have a conversation. On separate occasions in the summer of 2004, Mom and Dad told us that the Farm would be sold.

Why didn’t we discuss it as a family? In asking this question, part of me is angry. Why did they just tell us that they were selling without giving us much of a warning or a chance to come up with alternative options? Part of me is sad and filled with regret. Why didn’t I resist or argue or try to work with my sisters to create a plan for keeping the farm? Part of me is relieved. If we had kept the Farm, would my sisters and I have been able to negotiate and compromise with each other over what to do with the Farm and how to manage it? Would I have been up for the challenge of being responsible for the Farm, while struggling to manage my own aging house and raise two young kids? But, most of me is resigned to the belief that the Farm needed to be sold. It was no longer, and maybe never was, economically viable.

Is it viable?

a working farm no more

Judy’s version: Kully had to have some kind of livelihood. He decided in his mind that he wanted to become a bonafide farmer. So, he first started out with four white horses and a plow and then he finally got a Farmall tractor and he really desperately tried to make a living farming this place. And then during the Eisenhower years these small farms went under and in fact there’s still a copy of the letter that Kully wrote to Eisenhower begging him to change his farm policies.

Art’s version: When my grandparents had the Farm, there were many sons and daughters who were here and working on the Farm. When my dad took it over, it became basically a mom and pop and son operation with some outside help. But in the early 50s, the life of the small self-sustaining farm here in this community began to wane. Those were poignant moments during the Eisenhower administration. My dad wrote letters to Congressman Jerry Ford lamenting the plight of the small farmer and asking if anything could be done.

My grandparents didn’t sell the farm. They continued to live there for three more decades. But they sold their cows and stopped growing potatoes. Kully was elected Crystal Falls Township clerk. Ines worked at a gas company in Crystal Falls. Art went off to college, then seminary and graduate school. He only came back to the Farm for brief visits.

When Art and Judy inherited the property in 1992, it had not been a working farm for decades. Many buildings were falling apart. Rusting farm equipment littered the front 40 acres. Junk was everywhere—buried throughout the fields, tossed on top of the rock piles, cluttering up the Sauna.

When Art and Judy inherited the property in 1992, it had not been a working farm for decades. Many buildings were falling apart. Rusting farm equipment littered the front 40 acres. Junk was everywhere—buried throughout the fields, tossed on top of the rock piles, cluttering up the Sauna.

They worked hard and restored key parts of the property. They cleared out much of the junk. They got the Sauna working again. They hired a local handyman, Roland Cornelius, to help shore up the farmhouse. The former working farm was reborn as a family retreat space where third, fourth and fifth generation Puotinens would come to celebrate our heritage and retreat from our everyday lives.

All of this rebirth took a lot of money and physical effort. But, as they told me in their farm interviews, it was worth it because the Farm was important to us, the 4th generation. And it was worth it because of how keeping the Farm enabled them to honor the work and values of past Puotinens. My mom was particularly invested in honoring and being a part of the Puotinen heritage:

Judy Puotinen

But, was it really worth it? And was keeping the Farm the only way to honor and connect with past generations?

After several years of working, then briefly living, on the Farm, my parents came to believe that it was more of a burden than a treasure for our family. When they needed the money from the sale of the Farm in order to relocate for Art’s new job, they reluctantly sold it. While I miss the Farm terribly, I can understand their decision.

In revisiting the old stories and reading through the history of life on the Farm, I have been able to bear witness to the difficulties involved in trying to hold onto 80 acres of remote farmland and a handful of nearly century-old buildings. It not only depends on a lot of hard work, some grin-and-bear-it persistence (Sisu) and a strong commitment to preserving and maintaining the Puotinen heritage, which past and present Puotinens have demonstrated in abundance. It also depends on luck, health, a tremendous amount of money and a willingness to sacrifice (too?) many of one’s own desires and needs for the sake of holding onto the property.

The question of whether the Farm had been more of a treasure or a burden stopped mattering a year after my parents sold it. In October of 2005, my mom was diagnosed with stage four pancreatic cancer. She was dying. I forgot about the Farm as my family struggled to care for her and prepare for her death.

Restart Story

on not forgetting

Mom was diagnosed in early October of 2005 and died at the end of September in 2009. During much of the four years that she was sick, I couldn’t think about the Farm. It was too painful. My memories of the Farm were too connected to Mom and all of the time we had spent there together.

It’s hard to disentangle my feelings about losing the Farm from my feelings about losing Mom. Even though my dad grew up on the Farm and I’d heard so many of his stories about his experiences there, it was my mom who became inextricably tied to the land and the buildings. The Farm was meaningful because of her. She would talk with me for hours and hours, recounting stories about the Farm and its past inhabitants.

Video footage of my Mom and me, walking and talking at the edge of the front 40 field.

And, to some extent, my mom was meaningful because of the Farm. Of course there was much more to my relationship with my mom than our time at the Farm together. But, during my twenties, as I was trying to figure out how to be an adult, I visited the Farm with her. We bonded over hikes around the property and walks on the Bates-Amasa Road. And we spent a magical month in July of 2002, when I was 27, together at the Farm, exploring the property, the Amasa area and the UP.

What is the Farm and its stories without Mom?

A video memorial to my mom.

When my mom died, it took me almost two years to return to the upper peninsula to see the Farm and to visit her grave, located in Hematite Cemetery about a mile away from the property.

Why two years? We were supposed to bury her ashes together the summer after she died. Marji had arranged for us to release butterflies at her grave. To me, it seemed very important to say goodbye to her as a family in the space that mattered so much to her. We didn’t do it.

It was (and still is) difficult for me to get past our failure to bury her together at Hematite Cemetery.

Since my first return visit in 2011, I’ve gone back to the UP every year. I spend a few minutes at the gravesite and drive slowly by the Farm, marveling at all of the work the new owners have done to restore it.

I’ve also spent an increasing amount of time re-watching the old interview footage, re-reading my grandma’s memoir and other past documents and reviewing old photos. I’ve been using them to craft more farm stories and to aid me in my efforts to not forget the Farm. It’s working.

I used to worry that without a physical link the Farm, like the many different homes that I lived in and then left throughout my childhood and the friends that I made and then moved away from, would quickly be forgotten. And then eventually the world of the Puotinen Farm and the Sara-who-went-there-every-summer would no longer be imaginable. I’m not worried about that anymore.

I refuse to forget the Farm. And, as much I ache for the Farm property and wish I could experience its spirit and solitude, I don’t need to be at it to remember. Or to connect to the chain of past Puotinens.

The physical land and buildings may be gone, but my connection to the generations of people who lived there still exists. I’m accessing this connection through the footage and scrapbooks that I’ve collected and crafted into stories. And I’m working to strengthen my connection through storytelling.